We are all prone to certain biases when making assessments of any situation in life. Those biases can be magnified when dealing with money. Understanding our biases can help us all become better investors.

Table of contents:

- Belief Perseverance

- Information-Processing Errors

- Recency Bias

- When the Playing Field Shifts

- When Rational Becomes Irrational

- Loss-Aversion

- Overconfidence

- The Retirement Savings Crisis

- Regret-Aversion

- Consequences of our Biases

Belief Perseverance

I've often said the reason our method of active management has stood the test of time is due to the fact human emotions do not change. In school, on every single industry examination, in all the Wall Street marketing propaganda, and even in most regulations, we see a general lack of acknowledgement of these emotions. Traditional Finance, which has been drilled in all of our heads is based on what investors SHOULD do. Following the financial crisis we've seen a new branch of finance forming, Behavioral Finance, which is based on the study of what investors HAVE DONE (or are prone to do). This is brand new to nearly everyone in our industry, but I think it can completely change the way portfolios are constructed and how "success" is measured.

The first major studies on Behavioral Finance were not published until the late 1990s, but nobody started paying much attention until the mid-2000s. For those of us that have been at this game a long-time, this means we have a lot of catching-up to do. It also means we will all have to overcome our own biases in order to accept a new way of looking at the markets and our own investments (along with our clients.) The first step is simply understanding what some of the major biases are.

The first group of biases are Belief Perseverance. These are related to Cognitive Dissonance, which is mental discomfort when dealing with new information that conflicts with past beliefs. To deal with the discomfort, our brains tend to use the following biases:

Conservatism Bias

Conservatism Bias is a bias where we maintain our prior beliefs by failing to properly incorporate new information. We see this in action every day with both individual companies and the markets. New economic data or financial reports could mean a serious change in the long-term outlook, yet we tend to highly overweight the previous information and underweight the new. Mentally it is far easier to maintain the current view than to try to incorporate the new, often highly complex information into our outlooks. The most glaring example of this in the current market is the shift in Fed policy from "stimulative" to "tightening", something the market has not had to face since Allan Greenspan was in charge back in 2006.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation Bias is one way we deal with the new, complex information — we ignore it. Confirmation Bias seeks only information that confirms our previous belief and ignores anything that may conflict with it. We see this quite often with our political affiliation, but it exists in all aspects of life. Investors & analysts alike tend to only pay attention to information that falls in line with their outlook. They often ignore or explain away anything that conflicts with this.

Looking at the Fed, we again see a glaring example of Confirmation Bias. I've heard nearly every Wall Street analyst (who all tend to have a very strong bullish slant) use data showing how the market usually rallies when the Fed raises interest rates. Overall this may be true, but they are ignoring one key aspect — nearly all of the increase has been due to increasing earnings (since the Fed usually raises rates during a rapid recovery). The P/E ratio tends to fall fairly significantly during the rate hiking cycle as investors lower their "risk premium" under the assumption the Fed will raise rates too much and cause a recession. With earnings already slowing dramatically, it may be difficult for the market to rise with the Fed raising rates.

Representativeness Bias

Representativeness Bias is where we assign "new" information into categories based on our own past experiences. We see this happen quite often during a bull market. Every dip in the market is relatively shallow, so investors classify a sell-off as a buying opportunity. We also see a constant classification of what "year" the market resembles. So many people were burned by 2008 they are looking for similarities. Most often I hear analysts say, "housing is not in a bubble, so any correction won't be as bad as 2008." We also hear, "tech stocks aren't as overvalued as 2000, so any correction won't be as bad as 2000-2002." They are instead classifying any corrections into "2011" or even "1998" categories because those are ones most of us remember. (This also could be considered "Conservatism" as both 2011 & 1998 comparisons were quite bullish in the end.)

I rarely hear anybody use a 1936-37 comparison to the market even though fundamentally and technically we could be looking at something similar. Back then the Fed raised rates under the assumption the recovery was stable enough and they risked losing control of inflation. We of course know with hindsight the Fed did not have control of the situation (our final two Belief Perseverance Biases). The key takeaway from this bias is to look at ALL market history before classifying something into a particular category.

Illusion of Control Bias

This bias stems from people believing they have control of a situation or can influence the outcome, when in fact they cannot (study the history of the Federal Reserve for proof of this one). As investors, we tend to think we can control the direction of our investments, but we are truly at the mercy of the overall market. Sticking to longer-term, well researched strategies is critical to overcoming this bias as an investor. If you are a member of the Fed, I would encourage you to study this bias in much greater detail.

Hindsight Bias

This is probably the most difficult bias for us to overcome as investors. With hindsight we see past events as being predictable, which means it is reasonable that we "should have seen it coming". This leads us to believe we will see the next one coming and be able to avoid it (see the other biases above). This is the reason so many people are looking for comparisons of past market drops. The problem is the NEXT financial crisis and/or bear market is unlikely to be caused by the same thing that created the past two bear markets. As we are now working with our third teenage driver on getting his license we see an important lesson for investors — if you spend too much time focusing on the rear view mirror you will not see the danger IN FRONT OF YOU.

This is where the advantage of our method of Active Management becomes clear. We do not focus on our own opinions, beliefs, or analysis of the fundamental situation when making investment decisions. Instead, we can see the emotions of the market in the data coming out of the market as investors make their decisions. While the events or circumstances that cause the next bear market will most likely be different, our study of history says the market reaction to whatever the cause will be quite similar.

Information-Processing Errors

With everyone making their 2016 predictions, it is a good time to study the second group biases as they are all related to how we process information. While the first group, Belief-Perseverance, was more related to memory errors and mental mistakes in assigning probabilities, these biases are all related to how we process information and predict the future.

Anchoring & Adjustment Bias

Psychologists like to call mental short-cuts "heuristic influences", which are prevalent in many of our processing errors. The first short-cut comes when we have new, complex information to process. We need a starting point, so we typically pick the last known value, the current value, or some sort of average and adjust from there. The starting value is the "anchor". When we buy a stock we tend to anchor our assessment on the purchase price. If it is above, we made a good choice. If it is below we perceive it as a bad choice. (We see the same thing with account values. Regardless of the market environment, clients tend to base their assessment of their investments off the starting account value or some other "anchor" value they hit.)

[[NEED IMAGE]]

At this time of year we see it quite often as analysts work on their forecasts for next year. They take today's value, predict where earnings will be in a year, assign a P/E ratio, and then set a target price for the market. We also see analysts take the "average" return (somewhere around 10%) and then either forecast around that (above average, average, or below average). We can see the problem with anchoring bias just looking at the history of Wall Street forecasts. It is quite rare to see a Wall Street firm forecast a bear market. For the most part a "bad" year means one that is below 10% (the average). The "base case" is almost always for some sort of growth. Business Insider summed up the forecasts for 9 of the Wall Street firms over the weekend. Here is Goldman Sach's forecast:

[[NEED IMAGE]]

Looking at the forecasts, Goldman is actually one of the most bearish firms out there. With the S&P currently at 2080, their 2100 forecast for the end of 2016 is essentially flat. BMO Capital has a similar forecast. The others all range from "below average" around +6% to a few that are predicting "average" growth of 8-11%. What is really interesting is the earnings forecasts. The forecasts for earnings all range from $120-130, a 10-20% growth rate in earnings. The difference in price targets all stem from different P/E ratio assumptions. Lost in all of this is the fact the BASE CASE for Wall Street is 10% growth in earnings, which is right around the average growth in earnings the past 20-30 years. As we've mentioned many times, Wall Street can be quite wrong when it comes to their earnings forecasts, which means their price predictions are also quite wrong. This chart shows how wrong the so called "experts" have been in forecasting even the next 3 months' earnings.

Of course the real risk in Anchoring & Adjustment bias is what happens when the inevitable recession or bear market occurs.

Mental Accounting Bias

While mental accounting (segmenting money into different "buckets") can be helpful in setting up a portfolio, it can also lead to portfolios that are too heavily weighted towards one direction or the other. As humans we tend to segment our money based on where it came from. We might be careful with our salary, but if we receive a bonus we have a tendency to think of this as "free" money. Tax refunds are another example of mental accounting where we see most people spend their refunds rather than saving or paying off their consumer debt. We also see it when it comes to investing. People tend to think of their 401ks as "free" or "untouchable" money so often take extreme risks with that money, many times leaving a high percentage in their employer's stock. This magnifies the overall risk as what is typically their largest retirement asset is invested in the same company that provides their income. If something goes wrong with the company, both the current income and the retirement portfolio are at risk.

The best way to overcome Mental Accounting Bias is to look at all sources of income and all savings together and then build a portfolio that makes sense for both short, medium, and long-term needs.

Framing Bias

This is an interesting one that I think all of us in the financial industry need to look at closely. People tend to answer questions differently based on how it was asked (or framed). We also see it based on what time frame the investor "frames" the question in mentally (short or long-term). If a risk tolerance question centers around potential GAINS, investors tend to be willing to take on more risk. If it centers on potential LOSSES, they are far more conservative. Wall Street for years has focused on the potential gains, which has left too many clients with risks in their portfolio they are not even aware of. We try to offset that when working with new and existing clients by looking at both sides, but will be looking at ways we can do an even better job assessing risk tolerance in the near future.

There is one more Information-Processing Bias, but due to the details, I will hold off until tomorrow.

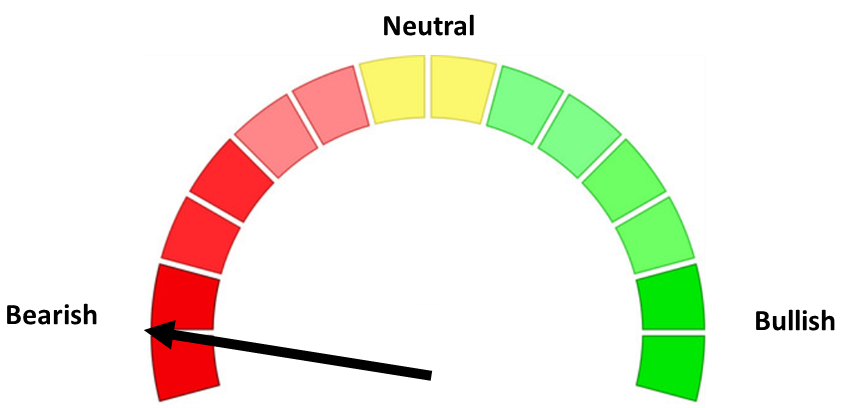

Recency Bias

Stocks, bonds, gold, & commodities all rallied on Tuesday following manufacturing data that showed an economy that could rapidly be heading towards a recession or at least a very low growth rate. This ties in closely with today's planned topic — Recency Bias.

I first heard our founder, Rick Gage, use the term Recency Bias back in 1999. He told me something that has always stuck with me. The human brain is conditioned to take the most recent situation and project it out indefinitely into the future. This causes investors in bull markets to take on far more risk than they can handle, but then in bear markets to become far too conservative to ever meet their investment objectives. Recency bias applies throughout our lives, from our assessment of our favorite sports team (Brock Osswieler is the next Peyton Manning…..wait, scratch that, Manning is a bum. He's the next Cam Newton), to our outlook on our children's future, to the weather, to the direction of our country, etc. It's just how our brains work.

As I was studying the Emotional Biases of investors I was excited to see psychologists actually defining the technical term for "recency bias" — Availability Bias. Availability Bias is the final Information-Processing Bias where individuals take a mental short-cut (heuristic) to estimate the probability using the information that comes most easily to mind. The way the human brain is programmed, the most recent information is easiest to recall. There are 4 sources of Availability Bias that apply to investing.

Retrievability

When an answer comes quickly to mind, more often than not we will assume that is the correct answer. This happens quite often in the investing world. The Wall Street firms have spent so much money advertising that investors tend to choose the "best" mutual funds based on how well known their brand is rather than the actual performance. We also see this when it comes to annuities, management fees, and active investing. With all the marketing dollars spent criticizing these things, investors have been programmed to look down on them regardless of what the long-term results say.

Categorization

This form of Availability Bias is closely linked to the Belief Perseverance Bias, Representativeness. When solving complex problems, individuals will group the data into simple categories that are familiar to them. We tend to assign markets to simple categories (bull or bear) or break them down into similar years for comparison (is it 1998 or 2011). We also tend to limit our investment options to categories we understand, which will limit our available investment options or cause us to be heavily invested in one category. For US investors that means a disproportionate weighting in Large Cap, US based stocks due to the belief the S&P 500 represents the "market".

Narrow Range of Experience

We are all prone to taking our own experiences and believe that is how the world works. This was clearly the case on Tuesday when nearly every asset class rallied on economic data that was highly disappointing. Over the last 6 years, bad economic news has actually been "good" news for the markets as it meant the Federal Reserve would be prone to creating more "stimulus". We also have witnessed a large number of people that believe the Fed will not allow a bear market or recession to happen since they have done "whatever it takes" to prevent this from happening the last 6+ years. This belief also falls under many of the Belief Perseverance Biases above.

Resonance

We all tend to believe the "world" shares our own interests and experiences. If we are struggling financially, we believe the rest of the economy is also struggling. If we have a strong interest in market behavior, we believe everyone shares this interest (which leads to writing 3000 words and counting in 2 1/2 days in a blog article). With our investments we have clearly seen how an individuals interest or experiences can slant both their risk tolerance and their choice of investments. This leads to over weighting (or under depending on the current trend) their own industry and shifting their asset allocation depending on how well the company they work for is doing. As the economy has improved and more people found work, we've seen a stark shift in investors' risk tolerance even though the economic cycle tells us we are probably near the end of the expansion cycle.

Consequences of Availability Bias

Availability Bias clearly has one of the most far reaching impacts on our investments. The markets move in cycles, but the longer one portion of the cycle continues, the more our brains believe "it's different this time." The "bad news is good news" thought process of the market is a perfect example. This mantra has gone on for so long it has led investors to believe fundamentals do not matter even though the long-term history of markets tells us the overall direction tends to follow the direction of economic growth. Yesterday's Manufacturing Surveys, which have historically been highly reliable leading economic indicators pointed to an economy that has not been this weak since the summer of 2012.

[[NEED IMAGE]]

Investors quickly recalled that the weakness then led the Fed to launch QE3, which created a rally in the market that matched the rally of the late tech bubble. Availability Bias quickly caused investors to believe at worst, the data means the Fed will not raise rates in two weeks and at best could mean QE4 is coming down the line. Nobody seems to want to look at the possibility the Fed still raises rates DESPITE a slow down in the economy.

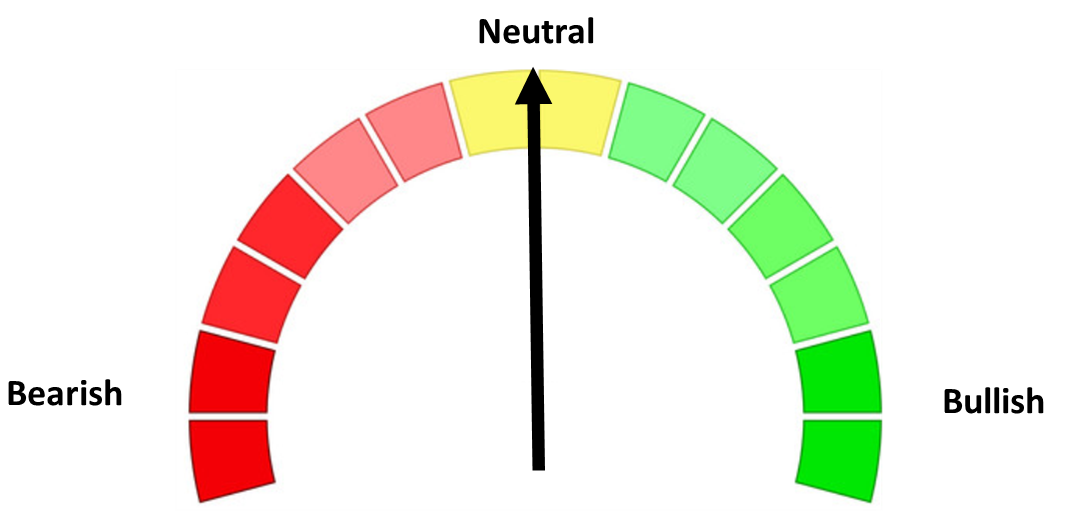

When the Playing Field Shifts

On Tuesday, the market was back in familiar territory — rallying strongly on economic weakness under the assumption the Fed would not raise interest rates when they meet in a couple of weeks. Who could blame them? For over 6 years every period of minor economic weakness was met with strong "stimulus" from the Fed. On Wednesday, stocks gave back all of their gains from Tuesday as Fed Chair Janet Yellen made it clear the weak data in manufacturing did nothing to sway the Fed's opinion that now is the time to move towards "normalization" in Fed policy.

All week we've been talking about two forms of Behavioral Biases, Belief Perseverance & Information-Processing Errors. All have centered around mental shortcuts (heuristics) & memory errors that result in faulty reasoning and analysis. Deep down our brains know we could be making mistakes, but the longer we go without any pain, the more we believe we are correct. The analogy I often use is one where we are purposely speeding on the interstate. The longer we go without seeing a police car (or getting a ticket), the more confident we are we will not get caught. However, when we see a car in the median our first reaction is to panic. In the same way, people that recently got a ticket for speeding are more likely to drive the speed limit, but the more time that passes since the ticket, the more likely they are to forget that "pain" and go back to their "normal" driving behavior.

[[NEED IMAGE]]

Investors behave the same way, which actually creates even more risk. The longer the market goes up, the more convinced they are it will not go down. This goes on until some sort of "scare" appears in the median and investors react by slamming on the brakes. Do you ever wonder why a Financial Crisis seems to happen at just the wrong time? It's all due to human behavior. Stability actually creates instability. The longer the financial markets go without a crisis, the more confident participants are convinced we will not see a crisis. The Fed realizes this which is why they may be raising rates despite evidence that shows we could be heading towards a fairly sharp economic slow down next year. The last 6 years of constant Fed "stimulus" has created so much instability that if too many cracks appear there will be nothing the Fed can do to prevent this. We are already seeing signs of this in the high yield market primarily due to the excessive lending that was done at relatively low rates in the energy sector.

Over the short-term, our Volatility Systems inside EGA & ARA is specifically designed to take advantage of short-term panic. It did just that yesterday, buying into the sell-off as investors quickly reversed their enthusiasm from Tuesday.

When Rational Becomes Irrational

Stocks, bonds, & the US Dollar were all hit hard on Thursday while commodities, precious metals, & the euro all staged a huge rally. The cause? ECB President Mario Draghi had been promising "big" measures to help combat lackluster growth in the euro-zone for the better part of the last 3 months. Most market participants expected this to happen at the conclusion of their meeting yesterday. When the ECB announced basically "more of the same" plans that has led to the world's 2nd or 3rd largest economy (depending on whether or not you trust China's "official" GDP numbers) teetering just above recession for the better part of 7 years now. The reaction in the markets was completely irrational, but that is what happens when something "everyone" expects doesn't happen.

All week we've been discussing Behavioral Biases, but we have only dealt with one specific classification — Cognitive Errors. These occur when seemingly rational people fail to follow rational decision making due to faulty statistical, information-processing, or memory lapses. For over 6 years we have been programmed to think it is "good" news for investors if the economy is "bad" and "bad" news if it is good. I only heard a few comments during yesterday's selling that maybe it is a good thing the Fed believes the economy is strong enough to handle a 1/4% interest rate increase and the euro-zone is not as bad as previously thought meaning they do not have to deploy the "bazooka" everyone has been expecting. It will be interesting to see how the market reacts to the November Payroll report scheduled to be released before the market opens.

While it does not help any of us on a short-term basis, the nice part about Cognitive Errors is they are easier to overcome than the Emotional Biases we will be discussing next week. With Cognitive Errors, the first step to not making them is understanding what they are and why we tend to make them. From there we can gather data beyond just the most recent bull market and especially beyond our investing memories. This is one of the key advantages of SEM's method of active management. Our system testing allows us to put ourselves back in time in all kinds of different markets to see when they will do well and when they will not.

As we mentioned in our most recent portfolio update, the last stage of the bull market (which can last 2-14 months) is typically the toughest for our systems. The reason can partially be explained by our discussion of the Cognitive Errors this week. When the environment changes and investors realize they may have made some errors, the reactions can be quite irrational. Both the size and duration of this irrational adjustment period are difficult, if not impossible to measure, so we are left sticking with the systems that have gotten us through the past bull/bear cycle changes (both in our real-time experience as well as back tested through other cycle changes throughout history).

Yesterday's "irrational" sell-off was considered a buying opportunity in our Volatility System inside ARA & EGA, adding additional exposure with the prospect of a quick, short-term return to more rational behavior.

Loss-Aversion

Last week stocks went on a seemingly irrational roller coaster ride that ended with the best single day rally since September (which was in the middle of a 12% sell off for the market). We also spent last week talking about Cognitive Errors, which are processing errors, mental short-cuts, and other mistakes our brains tend to make when processing information. Our Volatility System inside EGA & ARA took advantage of the irrationality and made a nice 2-day trade, which was closed on Friday afternoon. Some of the strange moves last week stem from these errors as everyone is struggling to find a period in the market that matches the one we are about to enter. We dove into this in greater detail during our Podcast last week:

[[NEED PODCAST LINK]]

This week we are going to turn our focus on another form of Behavioral Finance, Emotional Biases. Unlike Cognitive Errors, which can be somewhat overcome by studying historical data, Emotional Biases are much more difficult to correct because they stem from our own impulses or "intuition" that may not always be rational. The first stop is Loss-Aversion Bias.

Loss-Aversion Bias was first identified in 1979 by two psychologists studying prospect theory. It is something we have mentioned quite often as numerous other studies have also identified this bias. Essentially Loss-Aversion Bias tells us losses are far more powerful than gain psychologically. This chart from the CFA Level III Chapter on Emotional Biases illustrates the "utility" of gains and losses.

[[NEED PHOTO]]

This aversion causes investors to behave in ways that can have serious consequences on their portfolios. In a buy & hold stock & bond portfolio, studies have shown investors tend to hold on to their losers far too long under the belief their decision was not a "loss" until they "realize" actually sell the investment at a loss. On the other side, they tend to sell their winners far too quickly out of fear their profits may erode. This typically leads to undiversified, highly risky portfolios.

Loss-Aversion Bias also can tie in closely with the Cognitive Errors, Framing, Anchoring, & Mental Accounting which then creates Myopic Loss Aversion. Investors are often their own harshest critiques and also their own worst enemy. They often "evaluate" their decisions on short periods of time (often every time they receive a statement or at the end of a calendar year.) The "Framing" of the period often does not allow for a fair evaluation of the investment (unless it covered an entire market cycle). Some investments are designed to be "diversifyers" that help limit the downside, while others are designed to provide strong upside, but may have significant downside. The overall portfolio is designed to meet LONG-TERM risk/return characteristics but the time-frame may make either look unfavorable depending on when it is evaluated.

In addition, investors tend to "Anchor" their account value to the last evaluation period (again often the last statement). With that value in mind, they mentally consider that money to be the new baseline for their account (mental accounting). If the account moves below that value the investor may panic and want to lock in the "gains" by moving to "safer" or "better" investments. Again, depending on the time-frame, this will likely lead to an undiversified portfolio that does not come close to meeting the investor's overall risk-return objectives.

We will spend time at the conclusion of this series discussing ways to overcome some of these biases, but with respect to Loss-Aversion Bias it is impossible to completely remove it from the equation. At Strategic Equity we offer different programs that do well in different kinds of markets. We point out our "maximum drawdowns" in all of our materials showing clients what has historically been the worst loss from the highest statement value to the lowest. We've even recently added Modified Value at Risk which looks at possible future losses based on the risk/return profile of the investment. Knowing what type of losses are possible should help ease the pain when they eventually occur. Our disciplined approach also allows us the advantage of not falling prey to our own emotional biases when making decisions inside the portfolio.

However, due to other factors we will discuss later this week and depending on the "Framing" & "Anchoring" Biases that also enter the equation it is difficult to completely overcome loss-aversion bias. All we can do is try to think "rationally", look at the big picture, and realize that every investment has parts of the market cycle where they do well, and others where they do not so well. The critical question should be, does this investment match my long-term risk/return objectives. We have found that due to extremely high loss-aversion bias following the financial crisis, most investors ended up being TOO CONSERVATIVE with their investments, which left them expecting unreasonable performance from our Income Allocator and Tactical Bond programs especially with interest rates sitting close to zero for so long. While we are not advocating an immediate move into riskier investments such as our Enhanced Growth Allocator, it is something to consider during the next phase of the market cycle (the down one).

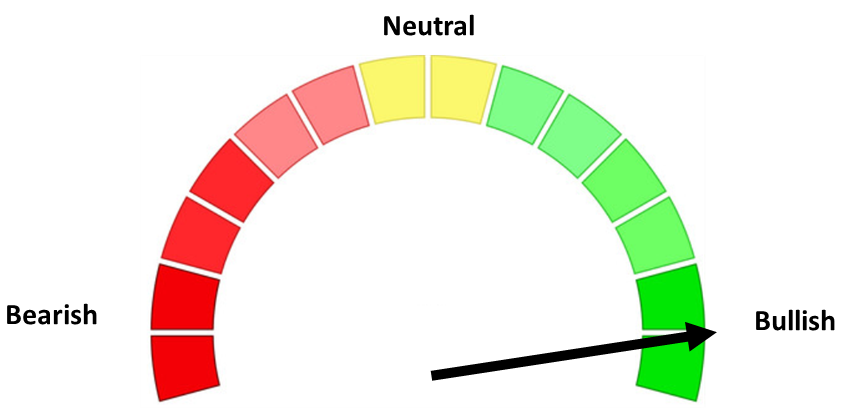

Overconfidence

This is the 3rd stock market bubble I've been involved in during my career. By far the Emotional Bias that appears most often in a bubble is Overconfidence Bias. This is also the easiest bias to understand when assessing others, but not as easy to diagnose on ourselves. Overconfidence Bias is an unwarranted trust in our own ability to assess situations, predict outcomes, & analyze complex situations. Overconfidence Bias can take two forms: prediction overconfidence & certainty overconfidence. While both have some Cognitive characteristics, it is our own emotions that place this in the Emotional category, which makes it particularly difficult to overcome completely.

Prediction overconfidence has some roots in the Cognitive Error, Anchoring & Adjustment as well as Representativeness in that our predicted outcomes all tend to stem from a certain starting point, average, or other base value and then we assign probable outcomes based on what we believe the current environment most closely represents. The problem with Overconfidence Bias is the distribution of likely outcomes tends to be both too narrow and skewed too heavily to the positive side. Remember, in 23 years of following the market I've never seen a major Wall Street firm predict either a Bear Market or a Recession. The "worst" they will predict is a "below average" year.

Certainty overconfidence is where investors really get into trouble. We tend to assign unreasonably high probabilities of positive outcomes. We believe we have more knowledge than other market participants. The certainty can actually be made much worse if we perform research that is tainted by such Cognitive Errors as Confirmation Bias, Conservatism, Anchoring, Framing & Representativeness. Many studies have been performed and my own experience confirms that the longer a market rises, the more overconfidence bias prevails in our assessment of the financial markets. I will never forget what one of my college professors told me (remember I went to college in the 1990s) — Don't confuse brains with a bull market.

The problem is as the market goes higher and the confidence investors have that there will not be a bear market, portfolios tend to shift far too heavily to risky assets. Few people understand that regardless of the current market environment, simple statistical theory tells us in any given year the S&P 500 can lose 35-40% (at a 95% confidence level). Overconfidence bias ignores this fact as we believe (fill in the blank) means we will not have a bear market any time soon. It is CRITICAL we all understand the consequences of Overconfidence and go back through both our own abilities to identify market trends (keeping in mind all of the Cognitive Errors, especially Availability (Recency) Bias & Hindsight Bias). Markets can & will lose money and those losses are likely to be far higher than what we predicted and most of the time more than we are comfortable with. Again, don't confuse brains with a bull market.

The last few weeks we are seeing what happens when "certain" outcomes end up being not so certain. I've been on at least 3 conference calls where I heard clients or advisors with confidence tell me China's problems were "contained", oil has "bottomed", and the market could "handle" a Fed interest rate hike. As data emerges that cause market participants to question this certainty, volatility ensues. This morning we are looking at a market getting hit with both a precipitous drop in oil prices and more carnage in the Chinese financial markets. This chart of oil from the past year shows how quickly markets can change direction.

[[NEED IMAGE]]

The more oil prices drop, the closer we get to seeing the collateral damage of Overconfidence Bias. Combined with low interest rates, lenders and bond market participants were so confident oil had a hard bottom (first at $80, then at $60, then $50, now $40) that we saw massive borrowing for oil exploration. A large percentage of high yield bond offerings are in the energy sector and we could start seeing widespread defaults in that space in the near future. Combine that with probable defaults in emerging market debt and we have a recipe for the next wave of the financial crisis.

Remember, the other side of Overconfidence Bias is Fear. Strategic Equity is here to manage these biases, but it requires humility and a long-term approach to not let our emotions derail our chances of success.

The Retirement Savings Crisis

You might wonder what today's title has to do with emotional biases. While I want to spend a great deal more time discussing our country's retirement savings crisis in the future, looking at the next 3 emotional biases immediately led me to think of the lack of sufficient retirement savings as the major consequence of all 3. According to a recent Forbes article, 30% of American households at or near retirement age have less than $10,000 saved for retirement. An additional 24% only have $10,000 to $99,000 saved, meaning over half of American households do not have sufficient retirement savings. Many people believe Social Security will take care of them, but ignoring the current sustainability of Social Security, the projected payments will not be sufficient to meet the quality of life many retirees expect. The lack of savings & reliance only on Social Security will put a large number of Americans in retirement at or near the poverty level.

[[NEED IMAGE]]

While solving the immediate issue will be a popular subject in the elections next year and beyond, it's not just the current generation of Americans at or near retirement that have failed to save sufficiently for retirement. This chart from the Employee Benefit Research Group (EBRI) shows the median retirement account balance by age.

[[NEED IMAGE]]

Again, we will hear a lot about the immediate reasons in the election (weak economy, failed policies of the (insert party name here), demographic shift, high corporate taxes, etc, etc.) but as we have been conditioned to do the past 30+ years, nobody wants to blame ourselves for the crisis. In my opinion and experience, a large portion of the retirement savings crisis comes down to the next 3 emotional biases:

Status-Quo Bias:

This is a bias where when given a choice, most people choose to not make a change. This means holding onto stocks or mutual funds far longer than they should. It also means not taking control of 401k or other retirement accounts when leaving an employer. We've also seen individuals that leave their 401k asset allocation the same as when they filled out the enrollment paperwork. Another by-product of Status-Quo Bias comes in the decision to sign-up for a 401k. While we are constantly reminding everyone the highest possible GUARANTEED return you can find is the employer matching contribution (a 100% return on your contribution), we still see most people choosing to keep their take home pay "as is" rather than finding 3-5% in their budget to maximize the employer match in their retirement account.

Endowment Bias

This bias stems from the perceived value something has based on whether or not we currently own it. We constantly see this with retirement accounts. "Well XYZ Company has done great, so I'll leave it as is." Often times the perception of doing "great" is a combination of other cognitive errors (such as not realizing a lot of the "growth" in the account came from contributions and employer matching) as well as the simple fact we spend far more time in a bull market than a bear. This means the perception of value has come from artificial factors without any real analysis. This "value" leads to individuals having accounts that are undiversified, spread around many different custodians, and often in funds that may not be suitable for their investment objectives.

Self-Control Bias

This bias is the result of letting short-term thinking take precedence over long-term thinking. We often hear, "I don't have enough money to save for retirement", but when we dig a little further we learn that either the individual has no formal personal budget or they are unwilling to make any sacrifices in their current living style to free up money so they can retire. We even see many individuals pushing back on finding the funds to at least take advantage of an employer matching contribution. As we mentioned earlier, our brains are programmed to focus on the shorter-term, which means we have to constantly remind ourselves of our long-term goals. When you combine self-control bias with other emotional and cognitive biases you see either a lack of retirement savings or a heavy focus on chasing short-term returns without regard to risk.

Combining Status-Quo, Endowment, & Self-Control Biases it is easy to see why individuals have insufficient retirement savings. As we are learning throughout this series, our brains can be our own worst enemies. Our goal at Strategic Equity is to help individuals overcome these natural biases by providing a well researched, disciplined approach to investing. Keeping track of the big picture is highly important in overcoming most of these biases.

(Allocation note: yesterday we received the final sell signal in our remaining high yield bond holding, which was "hedged" with a position in a Long-term Treasury fund. Both positions were closed in Tactical Bond & Income Allocator, leaving no CORPORATE high yield exposure in our programs. Tax Advantage Bond still has MUNICIPAL high yield bond positions, but those continue to track other municipal bonds rather than the corporate high yield bond market.)

Regret-Aversion

The final Emotional Bias is probably the most commonly observed one in my experience the last 20+ years. Along with Hindsight & Availability (Recency) Bias, both Cognitive Errors, Regret-Aversion Bias causes the most damage to long-term investment results. Regret-Aversion Bias is the fear of making a decision that turns out poorly. It is human nature to feel pain when we make wrong decisions. This fear can be paralyzing and can take on a few forms when it comes to investing.

The first is based on actions we COULD have taken. Closely related to Hindsight Bias the longer we see a decision we didn't make (not buying or not selling) go against us the more painful it becomes. The more painful it is to us, the more memorable this "error of omission" is, which means the more we are sensitive to not making the same mistake again. This often leads to staying out of the market far too long if an investor didn't sell ahead of large losses or staying invested in risky investments far too long if an investor previously missed a "buying opportunity".

The second form of Regret-Aversion Bias is based on actions we actually took. This "error of commission" has been found to be much more painful to us than an "error of omission" which can lead to being mentally paralyzed in making investment decisions. Investors that sold too early often will refuse to sell regardless of riskiness in the future. Conversely investors that bought into a market at a top are likely to refuse to invest in that market for a significantly long period of time. Regret-Aversion causes us to vow to "never make that mistake again."

There are two consequences of Regret-Aversion Bias:

- Overly conservative investments that do not meet long-term investment objectives. This is the result of the pain of past losses due to our decisions (buying near the top and/or riding the market all the way to the bottom.)

- Herding behavior. One way humans deal with Regret-Aversion is to simply do what everybody else is doing. We are under the assumption that if a lot of other people are investing in a certain asset class they must know more than we do. This is also a psychological way to prevent being "wrong" or at least being perceived as being wrong. Without endorsing Keynesian Economics, this quote from John Maynard Keynes comes to mind:

"Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally."

Out of all the biases we are clearly dealing with the consequences of Regret-Aversion Bias right now. A majority of our clients joined Strategic Equity following the collapse of the stock market in 2008-2009. The pain of realizing those losses led most to choose allocations that are far too conservative to meet their overall return objectives. Now that the market has been going up for over 6 years we see the other side of Regret-Aversion — Herding Behavior. Despite lackluster fundamentals the market has been driven higher. The longer the market continues to go up, the more other biases combine with the regret of selling at the bottom or not getting back in to the market during recent corrections.

At this point in the market cycle it is dangerous to follow the herd. A long-term approach is CRITICAL to success. Much better opportunities for gains will appear on the other side of the bear market. We are already seeing some of them developing in the high yield market as the fear of defaults in that space are escalating. To take advantage of these opportunities we must be PATIENT. The best way to deal with Regret-Aversion (and many other biases) is to look at the long-term data. We can see our income programs (Income Allocator and Tactical Bond) typically have relatively low returns for several years at the end of the market cycle. The circumstances in each of the market cycles have been different, but the dynamics have not.

As we've seen the past few weeks, market participants are struggling with an investing environment that promises to be much different than we've enjoyed the past six years. After celebrating the much stronger than expected payroll report on Friday with a 2% rally, over the past 3 days the S&P 500 has given back all those gains, closing yesterday just below the close last Thursday. Futures prices are again looking to start the day lower. Our equity programs still see little reason to worry over the short-term and actually increased the allocation a bit yesterday via our Volatility System. Before taking too much solace in the outlook for stocks, the bond market is much more pessimistic about the future which has led us to have no corporate high yield exposure. As I often say, bond investors are better predictors of fundamentals than stock investors, so any time bonds, especially high yields sell off like this I get worried.

That said, we have some interesting events just ahead of us. Our data tells us the "Santa Claus" rally typically starts late next week. A period of weakness is completely normal between Thanksgiving and the Santa Claus rally. The internal indicators have held up very well and from a technical stand point the market is still in a decent position. However, Janet Yellen and the Fed may play the role of the Grinch next week just before the Santa Claus rally should begin. We will discuss the Fed in much greater detail next week.

Consequences of our Biases

It is extremely difficult to overcome what comes "naturally". The goal of this series was to provide information on the most common "natural" biases that impact our investment results. Understanding those biases can somewhat prevent or at least diminish the consequences of letting our emotions control our decision making process. Remember there are two kinds of Behavioral Biases — Cognitive Errors & Emotional Biases. Cognitive Errors can be more easily addressed with data showing both the LONG-TERM history of an investment, both upside and downside risks as well as the CONSEQUENCES of allowing our emotions to dictate our assessment of the current investment environment. There is probably no better evidence of the consequences of our biases than the DALBAR Study of Investor Behavior.

[[NEED IMAGE]]

As a reminder, Traditional Finance is based on what investors SHOULD do. We are told stocks are the best place for our long-term money, which means we should ride out any losses (though Wall Street does a horrible job of setting the expectation of frequency and magnitude of losses). Behavioral Finance instead focuses on what investors ACTUALLY HAVE DONE. The DALBAR study gives us the evidence (and has for over 20 years) that investors are not capable of doing what Wall Street says they should do. The combination of Cognitive Errors and Emotional Biases has caused the average GROWTH investor to miss nearly half the upside of the market. For years we've shown this chart of the emotions that most investors feel as we go through the market cycle. It perfectly describes why the average investor has done so poorly.

[[NEED IMAGE]]

Next week we will have to turn our focus to the Fed, but in a future series we will begin discussing ways we can ADAPT to our natural biases in the way we structure portfolios. For the most part, Strategic Equity's method of management, portfolio construction, and daily oversight meets a lot of those criteria, although we all could do a better job of assessing risk & return objectives and using the understanding of individual biases to better structure a portfolio. As we head into the end of the year we all are naturally going to assess where our portfolios are and where we would like them to be. Remember Framing Bias is one of the Cognitive Errors we are prone to make. Using a simple "frame" for our assessment (such as a calendar year or a period that only includes a bull market) causes us to fall prey to other biases and often make decisions that have long-term consequences. Whether you are an advisor, SEM client or a buy and hold investor I'd encourage you to look at the BIG PICTURE and assess investments based on how they have done through a full market cycle (going back to at least the end of 2007.) This will require us overcoming our natural biases, but in the long-run you will be much better off.

Stocks broke their 3 day losing streak yesterday, but are going to get hit again this morning on the open. Remember, we could find out next week if we enter an environment investors have not experienced since 2006 — a "tightening" bias from the Fed. As the combined brains of market participants tries to adjust and set expectations volatility should be expected. We will talk about what that environment may look like next week.

Check back next week for additional updates.