Nothing makes you feel older than when you are using an example from something you lived through and realize the people you are talking to were in preschool when that event occurred. This has been happening to me more and more lately. The most recent occurrence was last month when I was teaching on Behavioral Finance at Liberty University and used an example from "The Big Short". As I received blank stares I realized the gap in our ages. When asked, only a handful of the students across two classes had ever watched the film. None had read the book.

I "assigned" the students to watch the movie over their Thanksgiving break. We did the same at our house. Cody & Dustin had gone through several viewings with me over the years. Even though they were in middle school when the events occurred, they are nerdy enough like me to take an interest in movies like this. Cody's wife said, "why don't I remember this happening?" and Cody replied, "well we were just starting middle school." An even bigger gap came from Toby when he said, "did this really happen?" I replied that yes, while they did embellish some things the overarching story is indeed true.

For everybody else in our household, a 5-6 year break from watching the movie was not enough to lure them back in even though we sold it with, "it has Brad Pitt, Ryan Gosling, Steve Carell, and Christian Bale!" That was again, not enough to hold everyone's interest. This year I did not pause it throughout to give an additional explanation or lesson during the key parts of the movie.

As coincidence would have it, the author of The Big Short, Michael Lewis has a Podcast (Against the Rules) and while driving Saturday Season 6, Episode 1 popped up next on my feed. This season Mr. Lewis is revisiting The Big Short. I listened to both Episode 1 and 2 on Saturday. Episode 2 included an interview with Greg Lippman. Mr. Lippman did not want his name used in the movie, but Ryan Gosling's character, Jared Vennett was based on his role, which was head of asset backed securities trading at Deutsch Bank. Essentially he was just pitching product to increase trading fees at his firm. The product he ended up pitching nearly wiped out his employer.

Mr. Lippman now runs his own hedge fund. During the interview he said something that we've always known, but I liked the way he phrased it:

"Human nature oscillates between fear and greed. During long periods of time when things are going well people become greedier and greedier."

He went on to talk about what happens inside financial institutions during these cycles:

"As perceived risks go down, the spreads between higher risk and lower risk investments decrease. In order to continue to attract money and generate the same "low risk" returns, institutions have to take greater and greater risks."

I think this is important to understand. The Financial Crisis and events discussed in The Big Short started 19 years ago. The losses began 17 years ago. Most "historic" returns only show 10, maybe 15 years. This means you have to be able to look at 20 year returns to see how those assets handled the last real crisis.

I'm in no way saying today matches the "greed" we saw in the housing crisis (nor the tech bubble), but keep in mind what I always say – history doesn't repeat, but it most certainly rhymes. The reason this is true is because human nature does not change. We all will cycle (with different degrees of variability) between fear and greed. When too many people cycle towards greed, the system eventually breaks.

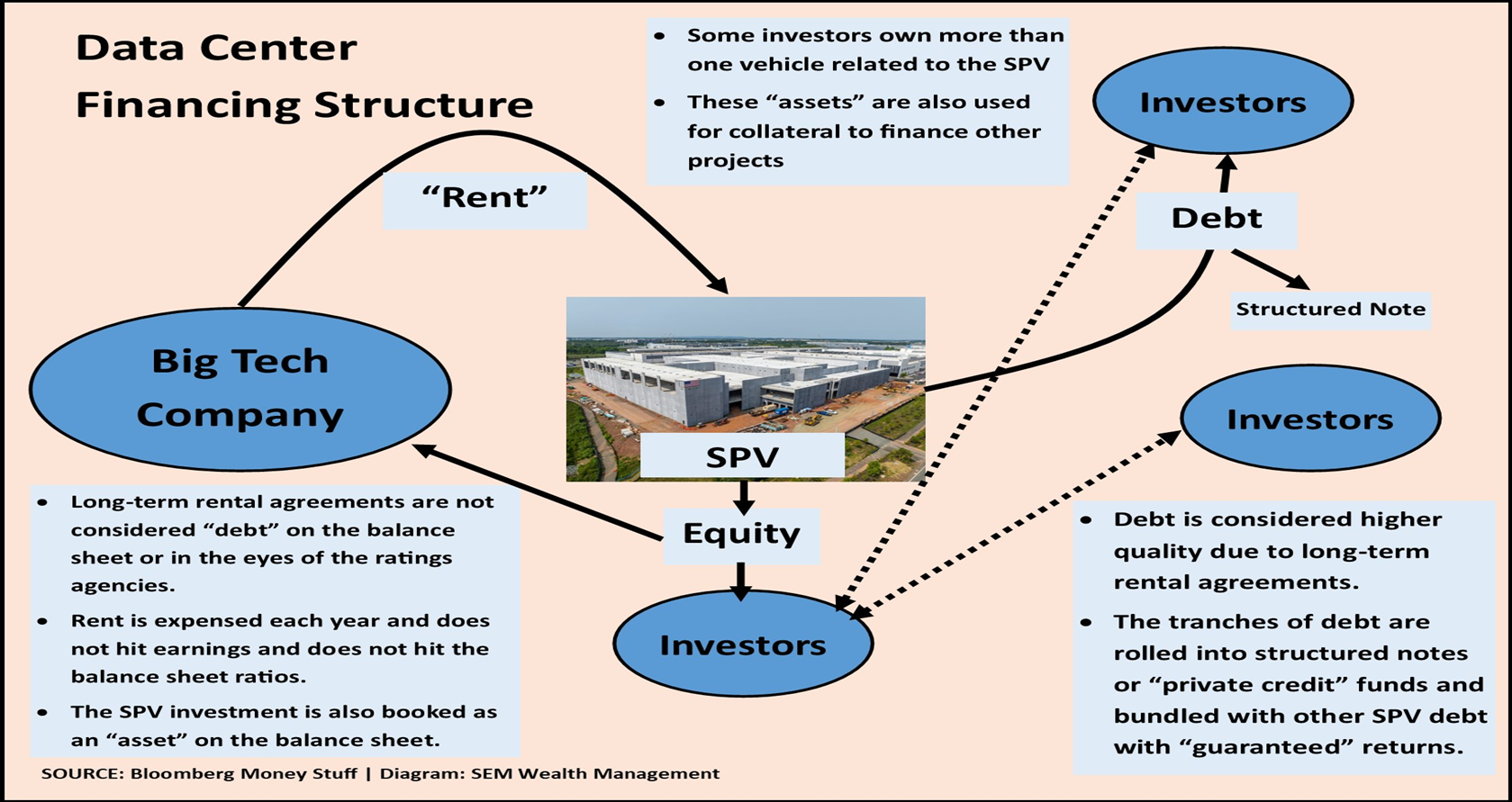

We've talked frequently the last few months about the "AI Bubble". A few times I've mentioned that I'm more concerned with the financing of the "buildout" than I am with the stocks participating in the bubble. Let's go back to what Mr. Lippman said on the Podcast:

"As perceived risks go down, the spreads between higher risk and lower risk investments decrease. In order to continue to attract money and generate the same "low risk" returns, institutions have to take greater and greater risks."

And then read this article from the Wall Street Journal:

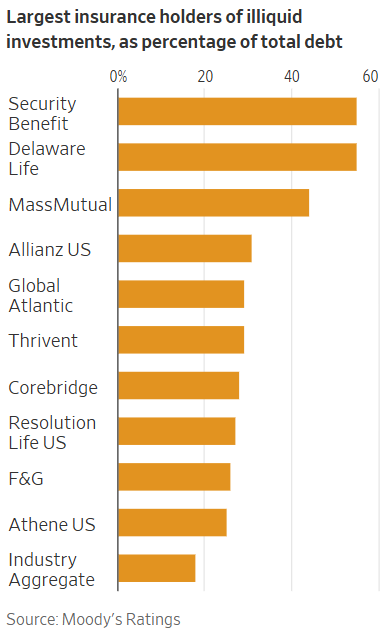

US Insurers are Binging on Private Credit Moody's Says

Risks are perceived to be low. Spreads are tight. Institutions (such as insurance companies issuing "guaranteed" payment products) need to continue to generate returns high enough to attract more money. As always, Wall Street has been there to meet this demand. Look at this list. If you're an advisor, chances are you've had wholesalers from these firms reaching out to you to pitch their products, they might not be as slick as Ryan Gosling's Jared Vennett, but we do have to remember they are compensated based on how much money you invest in their products so are obviously not the most independent of sources.

I picture private credit being pitched by hundreds of "Ryan Goslings" representing the biggest Wall Street firms. They don't care about the end result, only that they can carve up a bundled bunch of payment streams into a vehicle the ratings agencies say is "AAA". Here is a chart I will be using in our webinar on Wednesday:

Speaking of our webinar, don't forget to sign-up. Even if you cannot make it, signing up ensures you receive the replay.

This topic deserves its own post or even its own research paper. Again, I'm not saying this is the Financial Crisis or Tech Crash. Remember, history doesn't repeat, but it most certainly rhymes and this is looking more and more like something Dr. Suess could write about.

An Efficient Market?

One of the chapters I teach on at Liberty is "stock valuation". Academics like to tell us that the price of a stock represents all "known" information, especially for the largest companies. Each semester I teach I can find a recent example proving how sensitive this "efficient" market is to the slightest change in "known" information or expectations. Last week we could look to Alphabet (Google) and Nvidia as yet another example of a very inefficient market.

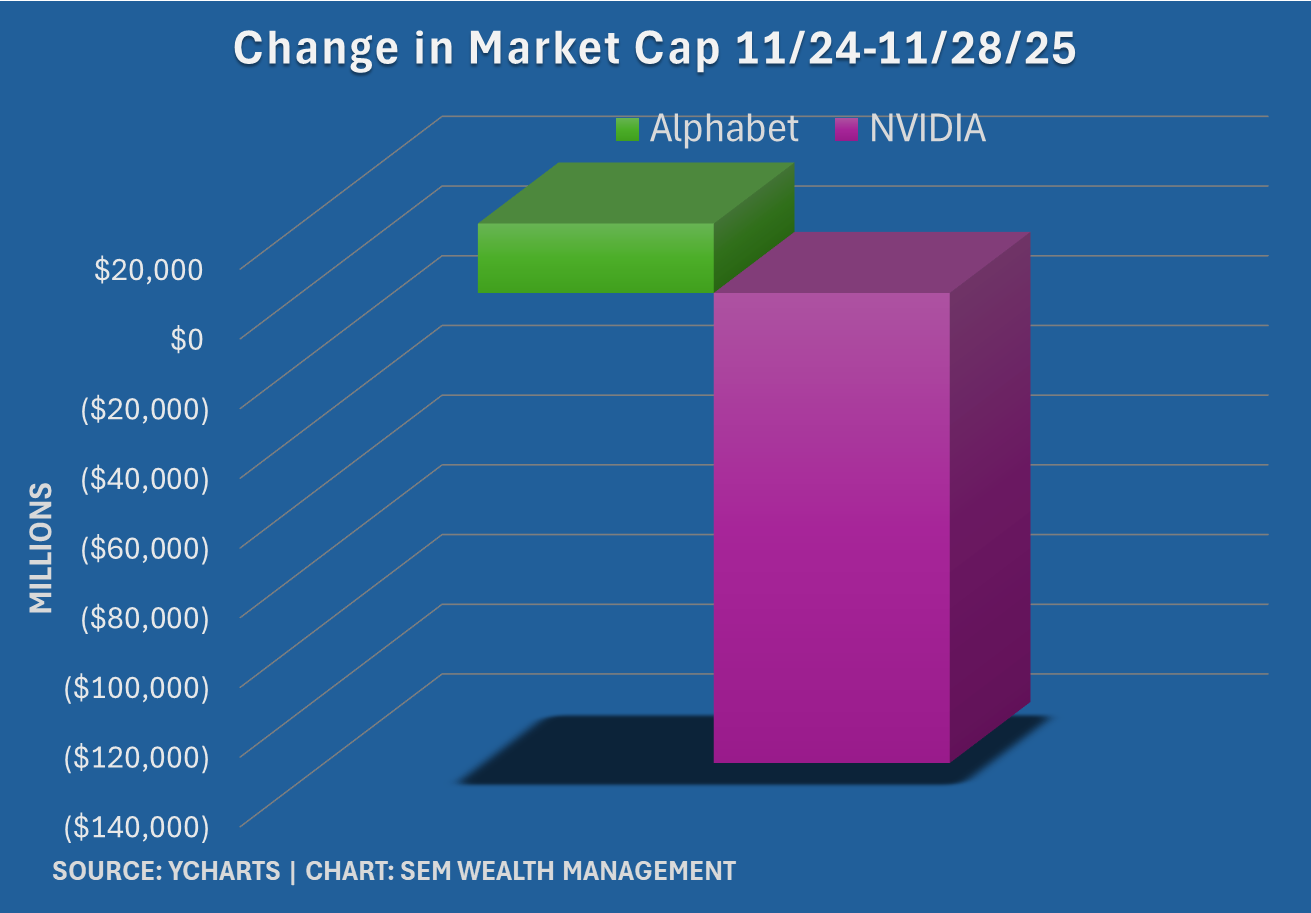

Last week, Reuters reported Meta was in negotiations with Google on a "multi-billion dollar" deal for its Tensor Processing Units. Google would first rent out its chips as early as 2026 to Meta for use in its Data Centers, with Meta then shifting to purchasing more chips in the future. The market reaction was not proportional to the news. On the day, Google gained $62 Billion in market cap while Nvidia lost $115 Billion. One of the issues I've had with AI "bubble" is the "circular" financing where the "hyperscalers" are buying, selling, investing, and leasing from each other. One company's "expense" or "capital expenditure" is another company's revenue, but yet all the stocks go up when a deal is announced.

For the week, Google gained nearly $20B in market cap while Nvidia lost close to $135B.

Yes I know there are other adjustments happening, but this is the risk of investing in a mania. The market believes last week's news is worth just $20B to Google, which theoretically is their ability to steal market share from Nvidia. Nvidia's lost market share, however, was believed to cost them $135B. Something doesn't add up here. Either the Nvidia drop was a severe overreaction, Google's pop was too small, or Nvidia was so overvalued, the slightest attack on their market share is a sign of too much speculation inside the stock. (This is definitely not a recommendation to buy or sell any of these securities.)

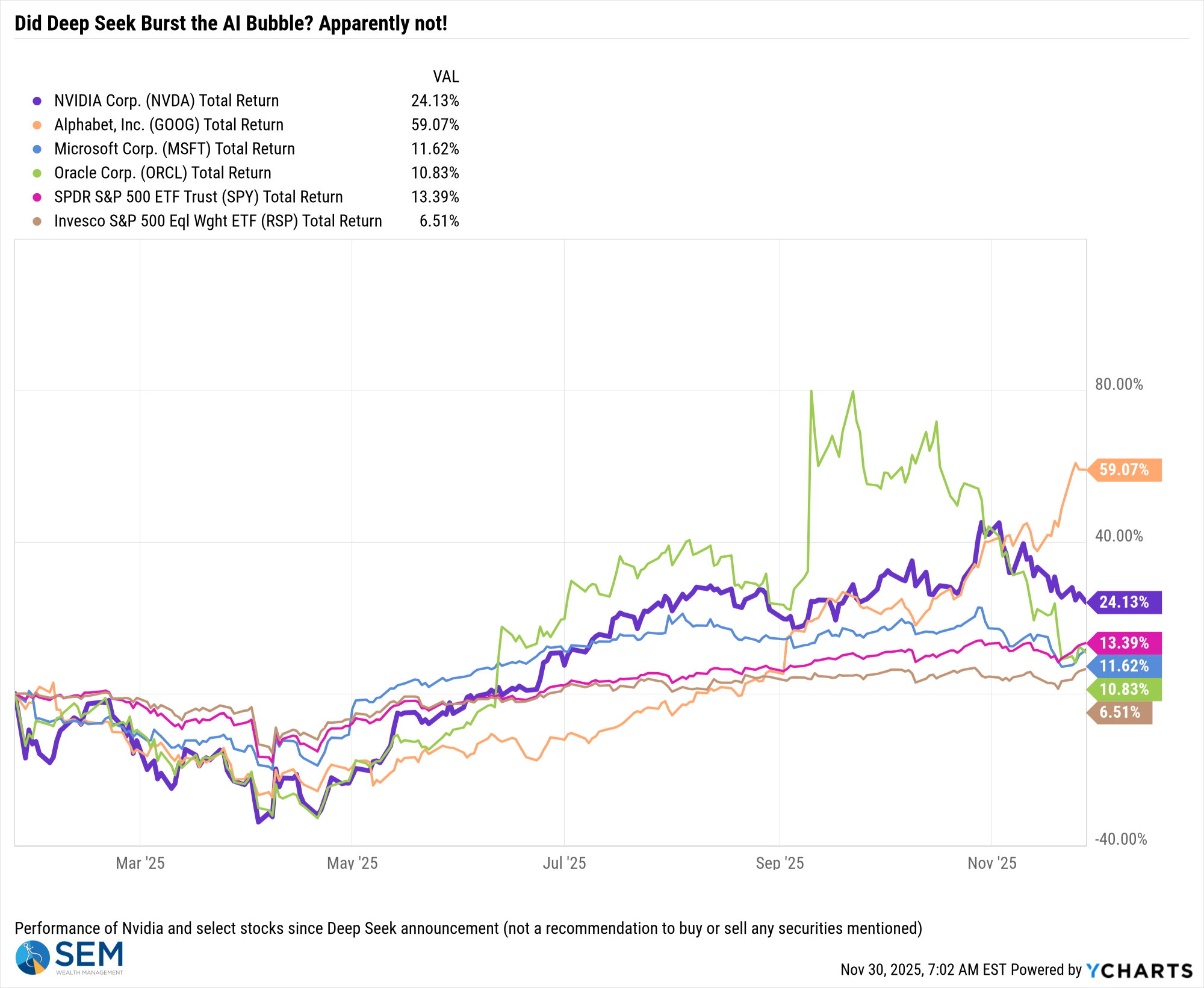

This of course isn't the first attack on Nvidia's perceived dominance. It's hard to remember, but at the start of the year Deep Seek's announcement on a much cheaper LLM model hit Nvidia and other AI-related stocks. We've also seen Oracle go through a temporary surge only to give up all those gains.

I have a lot more on my mind, but with lighter volume last week and a new month which will include a Fed meeting, several rounds of "new" economic data, and I'm sure more market moving AI announcements, I think I'll stop here.

Market Charts

Note: "last week" is the last 5 trading days. I cannot get Y-Charts to only show the actual WEEK and "4-days" is not an option.

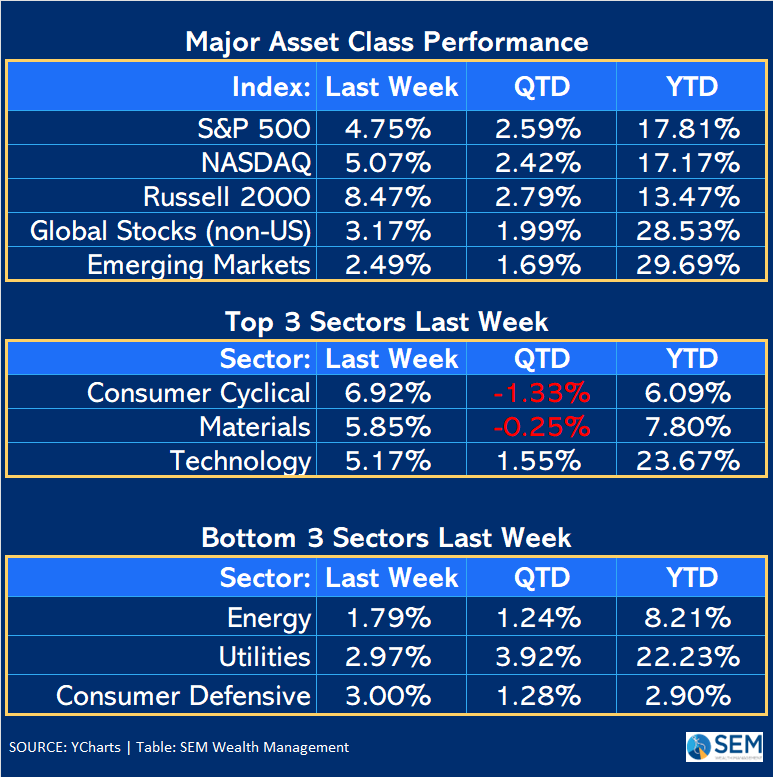

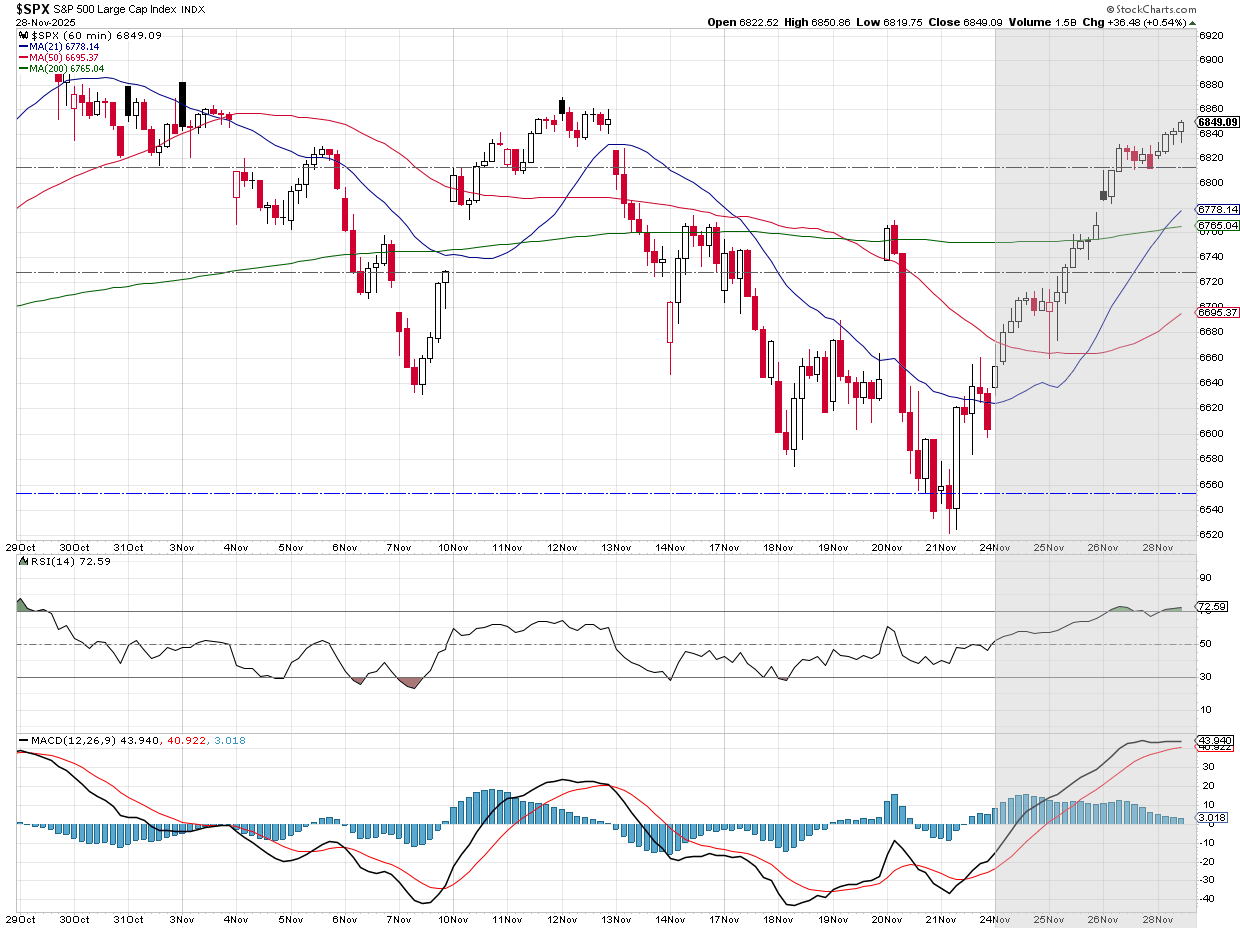

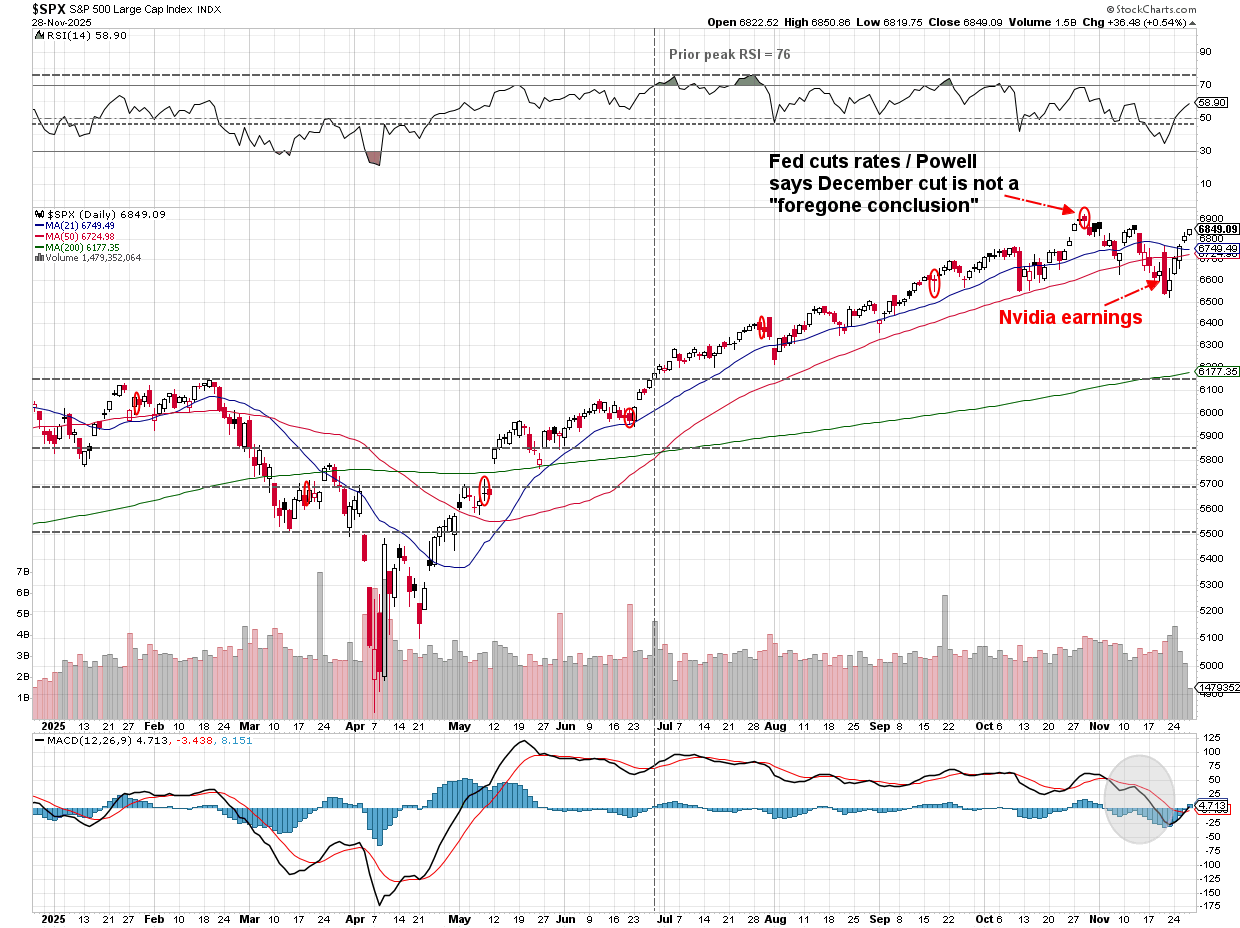

The stampede off the lows from Friday, November 21 continued all week.

The market is nearly back to where it was after the last Fed meeting, now that there is over a 90% probability priced in for a December rate cut.

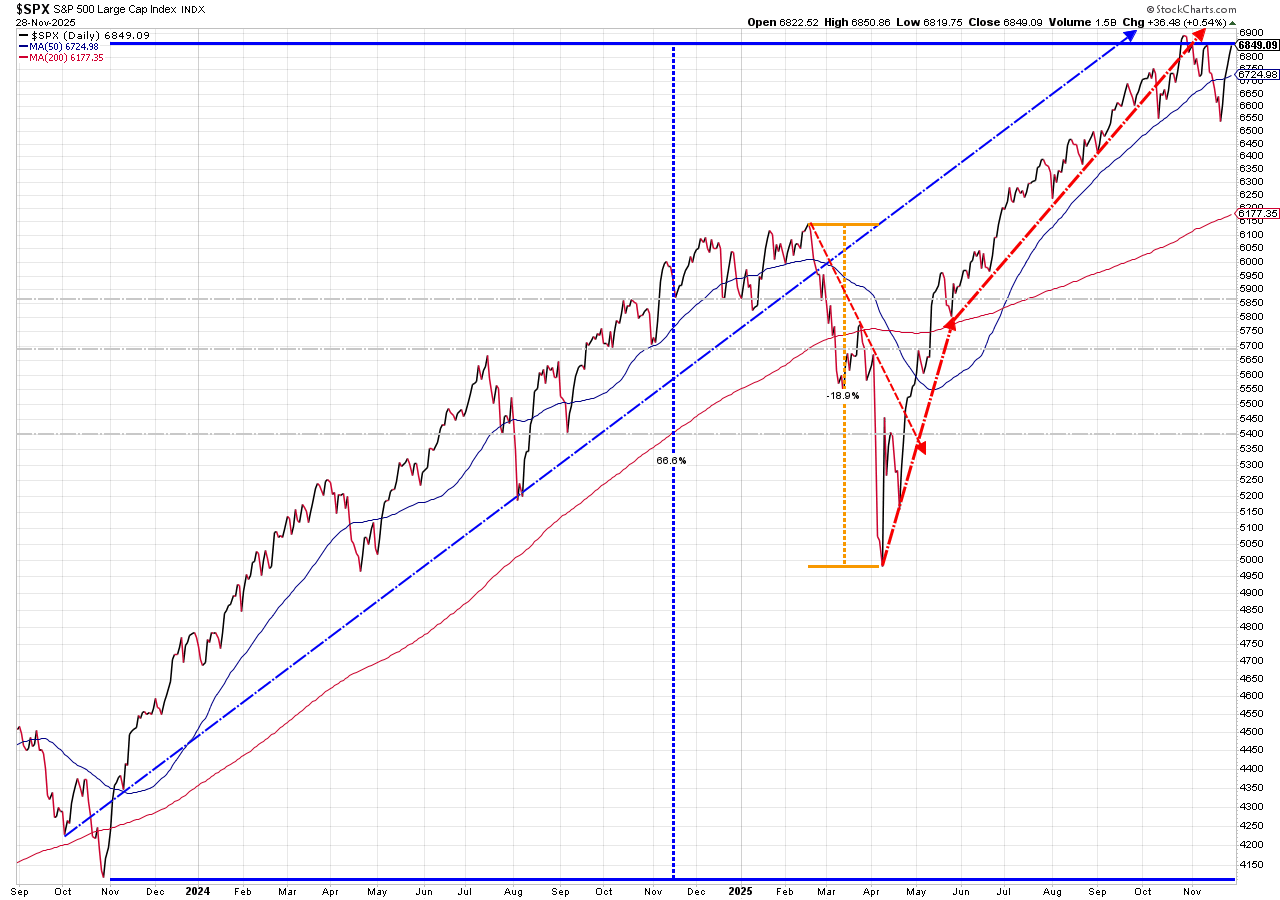

Maybe it is all about the Fed and nothing else matters. The market is up 67% in a little over 2-years after the Fed announced the end of their rate hiking cycle.

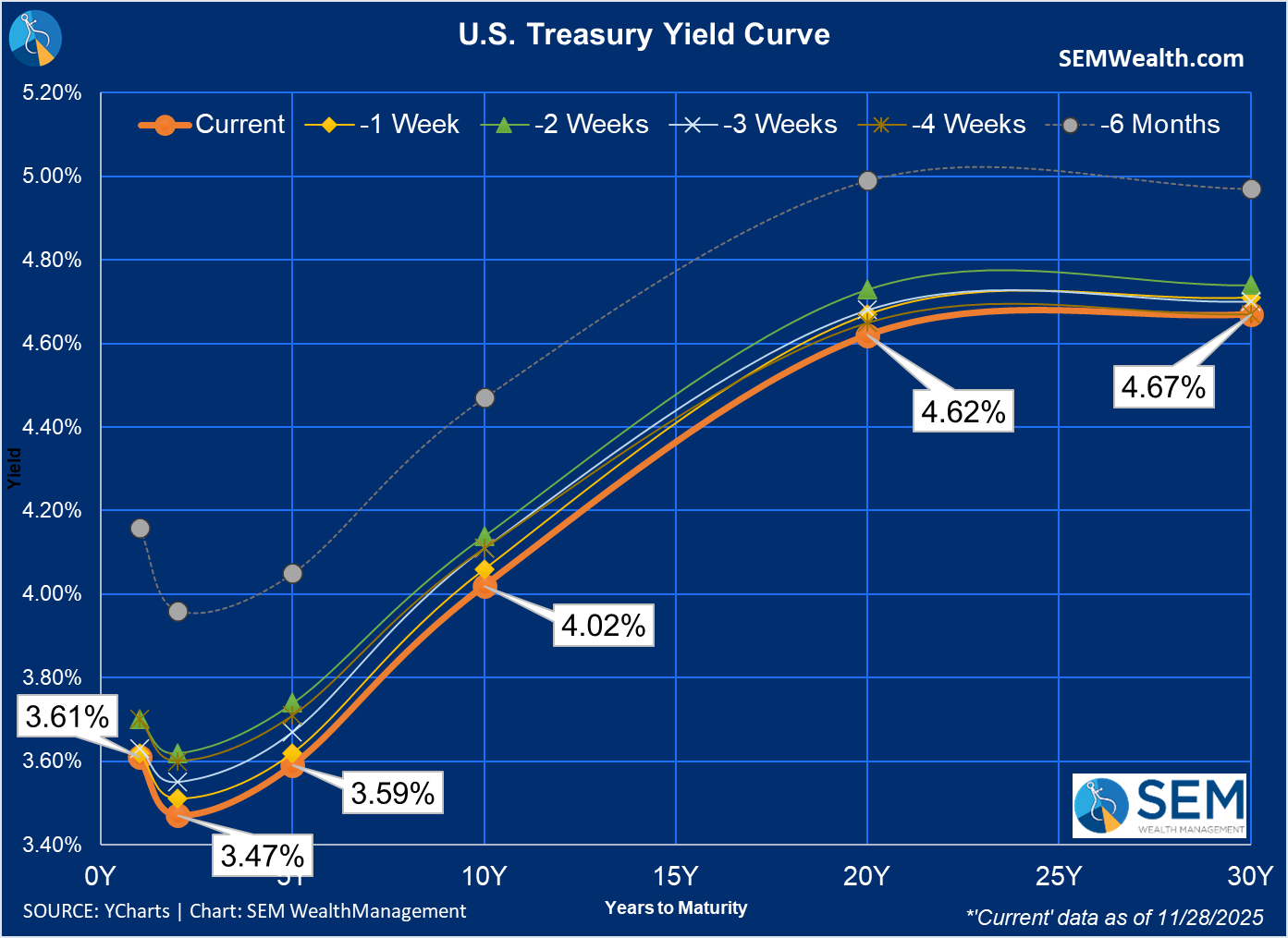

With unemployment barely ticking up and inflation still stubbornly high, the bond market is the area to watch. Last week rates hit their lowest levels since October.

The 10-year Treasury crossed below 4% briefly on Friday before closing just above that key level.

SEM Market Positioning

| Model Style | Current Stance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tactical | 100% high yield | High-yield spreads holding, but trend is slowing-watching closely |

| Dynamic | Bearish | Economic model turned red – leaning defensive |

| Strategic | Slight under-weight | Trend overlay shaved 10 % equity in April -- added 5% back early July |

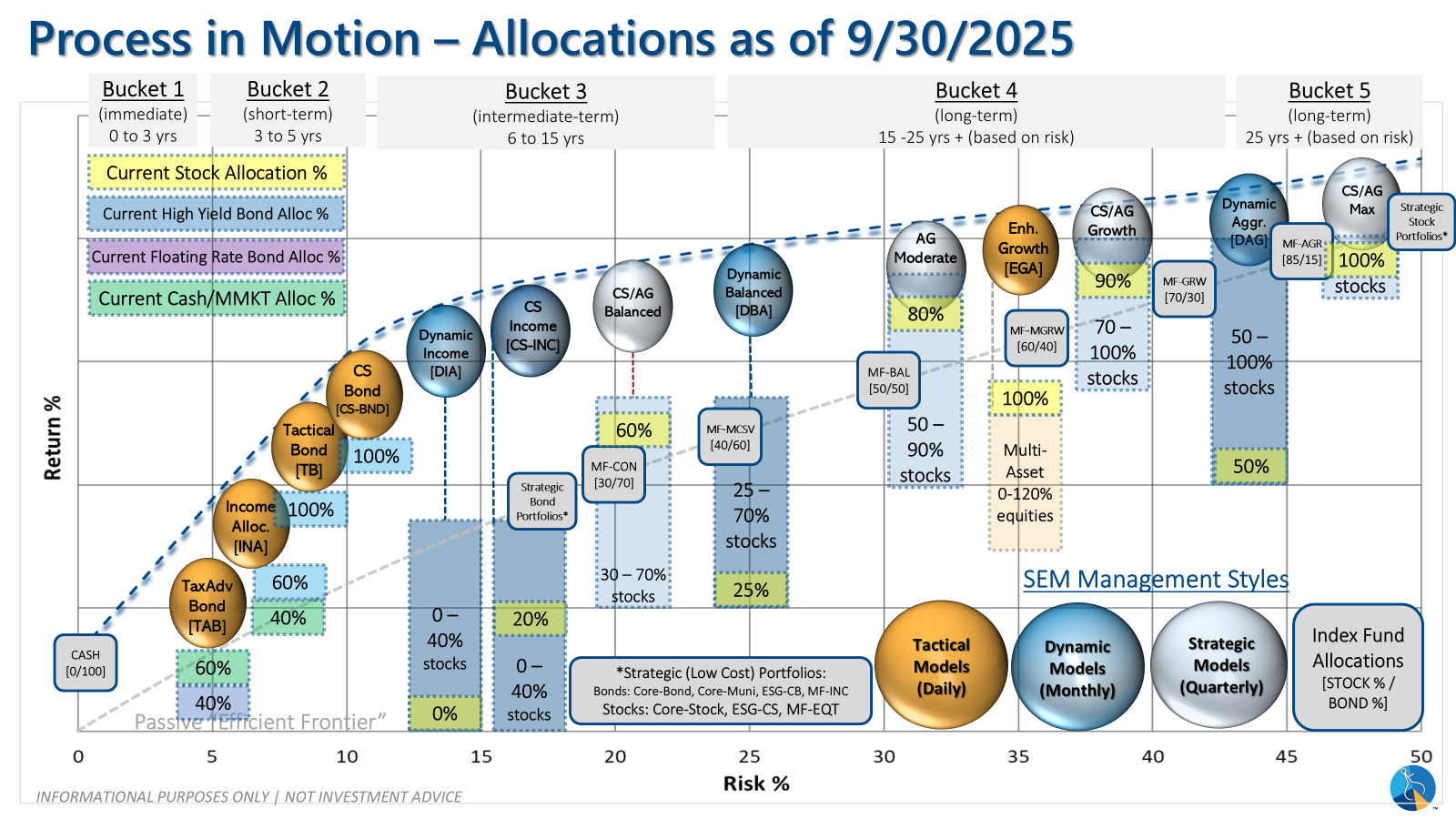

SEM deploys 3 distinct approaches – Tactical, Dynamic, and Strategic. These systems have been described as 'daily, monthly, quarterly' given how often they may make adjustments. Here is where they each stand.

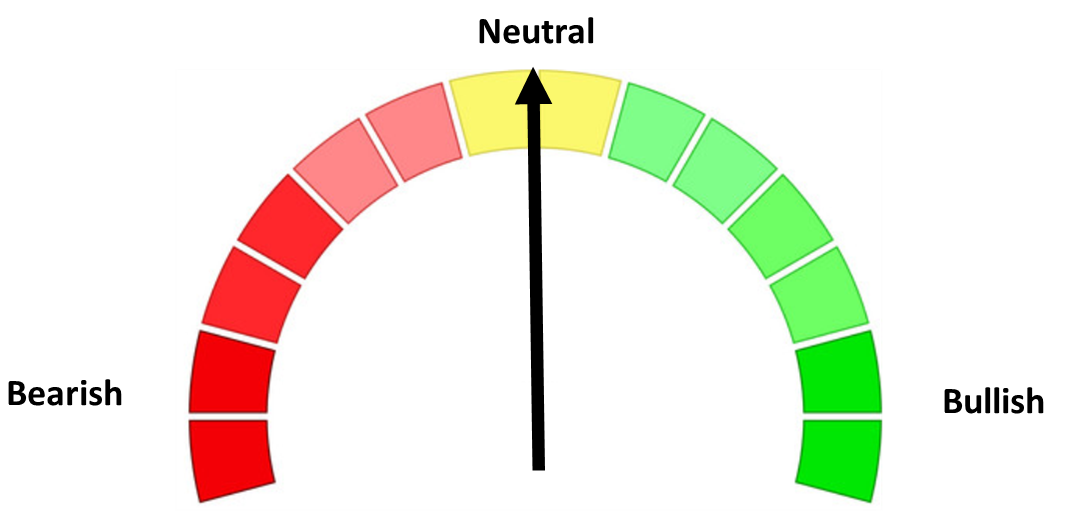

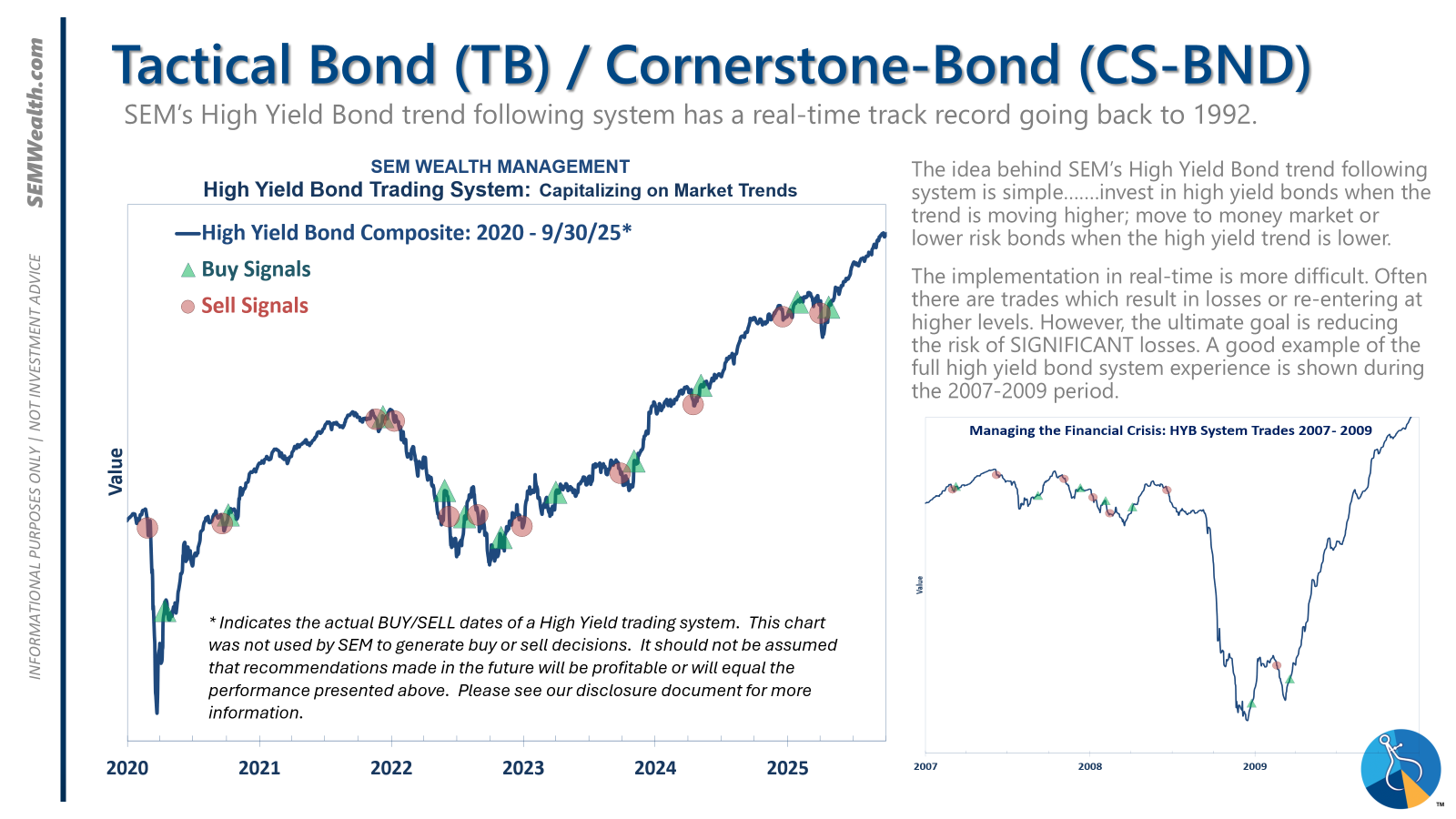

Tactical (daily): The high yield system has been invested since 4/23/25 after a short time out of the market following the sell signal on 4/3/25.

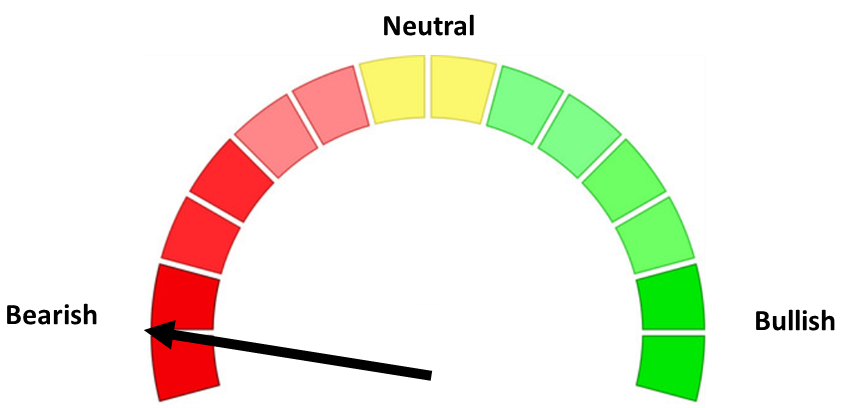

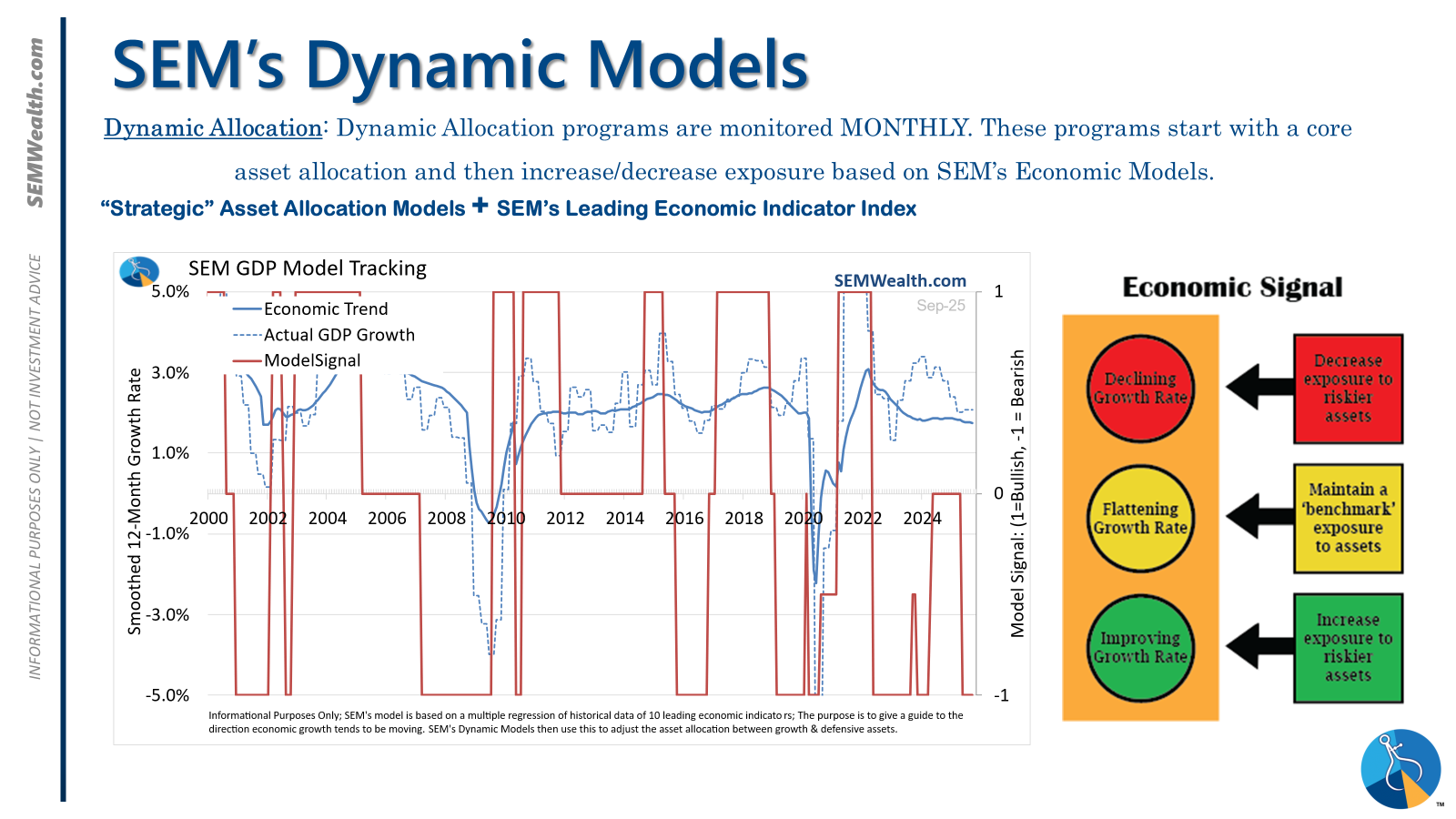

Dynamic (monthly): The economic model went 'bearish' in June 2025 after being 'neutral' for 11 months. This means eliminating risky assets – sell the 20% dividend stocks in Dynamic Income and the 20% small cap stocks in Dynamic Aggressive Growth. The interest rate model is 'bullish' meaning higher duration (Treasury Bond) investments for the bulk of the bonds.

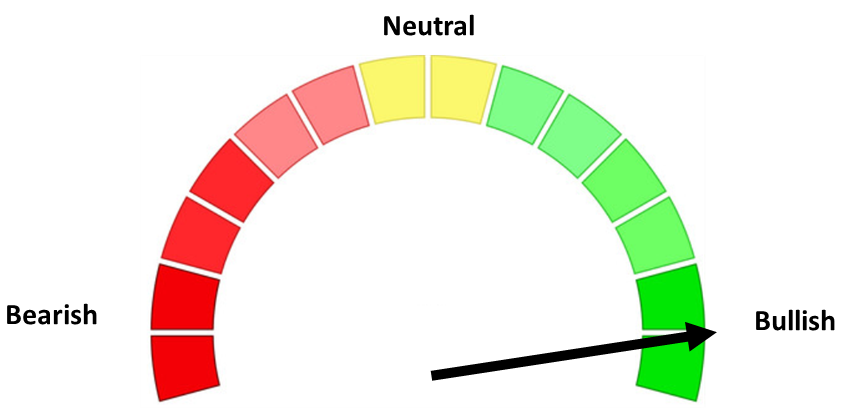

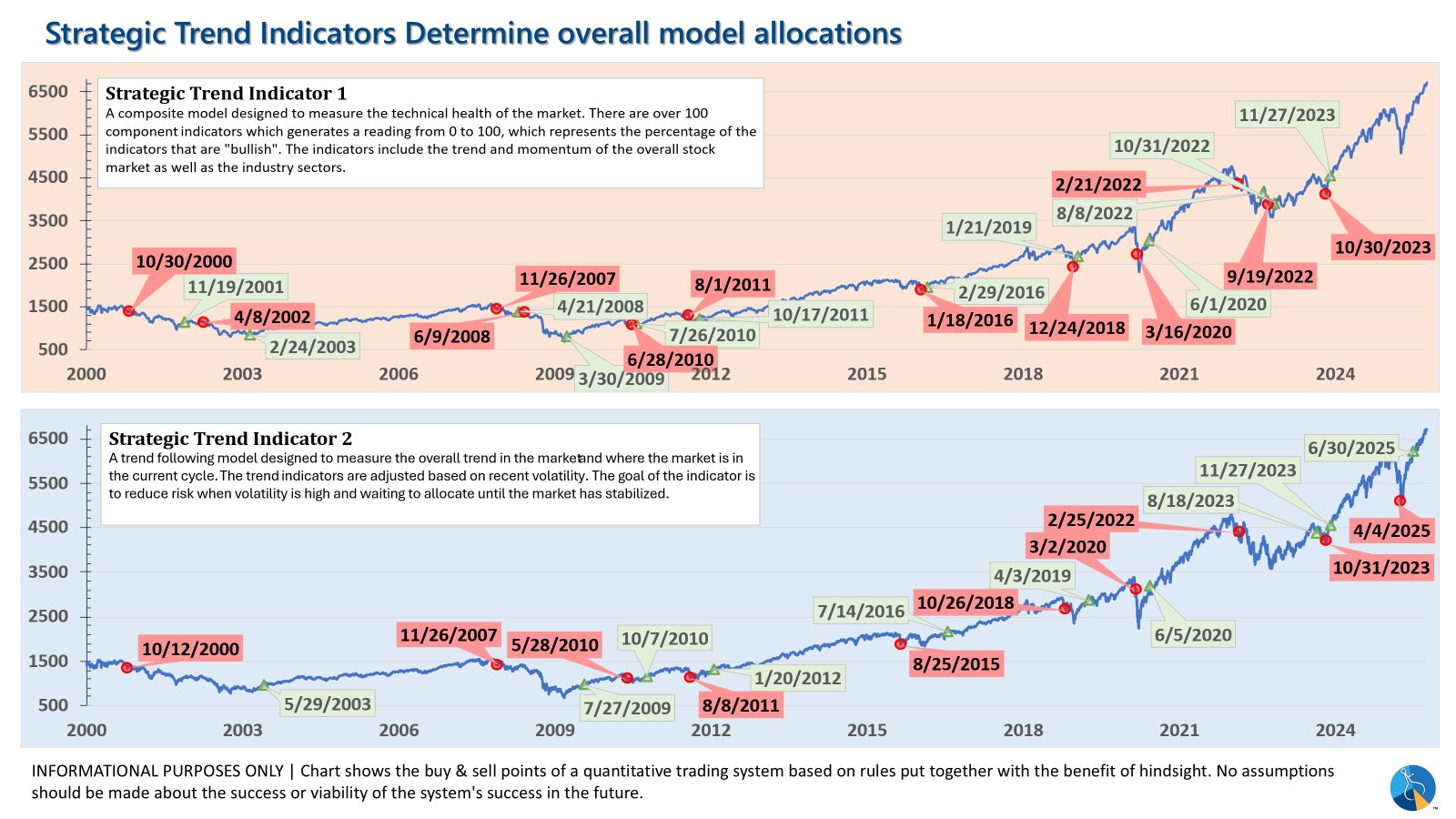

Strategic (quarterly)*: One Trend System sold on 4/4/2025; Re-entered on 6/30/2025

The core rotation is adjusted quarterly. On August 17 it rotated out of mid-cap growth and into small cap value. It also sold some large cap value to buy some large cap blend and growth. The large cap purchases were in actively managed funds with more diversification than the S&P 500 (banking on the market broadening out beyond the top 5-10 stocks.) On January 8 it rotated completely out of small cap value and mid-cap growth to purchase another broad (more diversified) large cap blend fund along with a Dividend Growth fund.

The * in quarterly is for the trend models. These models are watched daily but they trade infrequently based on readings of where each believe we are in the cycle. The trend systems can be susceptible to "whipsaws" as we saw with the recent sell and buy signals at the end of October and November. The goal of the systems is to miss major downturns in the market. Risks are high when the market has been stampeding higher as it has for most of 2023. This means sometimes selling too soon. As we saw with the recent trade, the systems can quickly reverse if they are wrong.

Overall, this is how our various models stack up based on the last allocation change:

Curious if your current investment allocation aligns with your overall objectives and risk tolerance? Take our risk questionnaire